As the Anniversary of this accident and resulting disaster approaches (1912) this is a good time to consider the fact that the accident itself as in all accidents stems from both poor design; an initial unforeseen incident (in this case there was an unprecedented block of ice which broke free from the Northern Ice fields and an unusually high tide which lifted the iceberg from its anchored position) and then a chain of human error resulting from both design flaws (technology too complex relative to the human training & experience). There is NEVER one person to blame and always many factors that occur all at the same time. The most important thing is for engineers, designers, ergonomic experts to perform a root cause analysis, learn and then apply to future design, training and testing. Titanic was a good teaching opportunity with a huge loss of life.

Here is an excerpt from the UK’s Telegraph (who interviewed the grand daughter of the senior most officer who survived the sinking, Louise Patten) which not only gives us a different take but also shows how the public and even Inquiries too often try to blame one “fall guy” for the disasters which occur at our peril. To overlook the correct method which is a thorough Root Cause Analysis (this is taught very early on in University Level Ergonomic courses) and not patiently review all of the data prevents us all from really learning from an accident or even an near miss so as to lower the chances of a similar accident from occurring. The other critical part of the story is something only now being applied in some hospitals in Canada relative to patient death’s following a string of errors; fellow employees will often not come clean about accidents which occur as they fear the loss of theirs and their fellow employees jobs, and Senior Managers try to cover up the truth so as to limit financial and reputational liabilities. This is in large measure why mistakes and accidents keep repeating themselves in the workplace.

Excerpt from the UK Telegraph Week of April 9th 2012

“But can there really be anything new to say, almost 100 years on, about the Titanic? ‘My grandfather was the Second Officer on the Titanic,’ Patten explains. ‘He was in his cabin when it struck the iceberg. Afterwards, he refused a direct order to go in a lifeboat, but by a fluke he was saved.’

Related Articles which reveal our propensity to blame one or two causes and the human factor instead of design, poor training, lack of time to allow experts to be developed

- 30 seconds that sank the Titanic

04 Dec 2011

What then did he know that he wasn’t telling? ‘After the collision,’ Patten goes on, ‘my grandfather went down with the Captain and Murdoch to Murdoch’s cabin to get the firearms in case there were riots when loading the lifeboats. That is when they told him what had happened. Instead of steering Titanic safely round to the left of the iceberg, once it had been spotted dead ahead, the steersman, Robert Hitchins, had panicked and turned it the wrong way.’

At first glance it sounds extraordinary that anyone – much less the man put in charge of the wheel on the maiden voyage of what was then the world’s most expensive ocean liner – could have made such a schoolboy error. But, Patten explains, there was a very particular technical reason for this otherwise incredible error.

‘Titanic was launched at a time when the world was moving from sailing ships to steam ships. My grandfather, like the other senior officers on Titanic, had started out on sailing ships. And on sailing ships, they steered by what is known as “Tiller Orders” which means that if you want to go one way, you push the tiller the other way. [So if you want to go left, you push right.] It sounds counter-intuitive now, but that is what Tiller Orders were. Whereas with “Rudder Orders’ which is what steam ships used, it is like driving a car. You steer the way you want to go. It gets more confusing because, even though Titanic was a steam ship, at that time on the North Atlantic they were still using Tiller Orders. Therefore Murdoch gave the command in Tiller Orders but Hitchins, in a panic, reverted to the Rudder Orders he had been trained in. They only had four minutes to change course and by the time Murdoch spotted Hitchins’ mistake and then tried to rectify it, it was too late.’

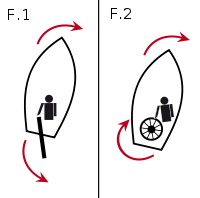

This pictograph reveals how the steering using Rudder Orders is the opposite to the steering of Tiller Orders. This coupled with a lack of training and experience with the running of the Titanic leads to errors and this case the “perfect storm”. Lesson learned? Never be the first to use new technology!

A second and potentially even more damning secret; if the steersman Hitchins had made a human error, Bruce Ismay, chairman of the White Star Line, owners of the Titanic, and another survivor of the sinking, gave a lethal order.

‘Titanic had hit the iceberg at her most vulnerable point,’ explains Patten, ‘but she could probably have gone on floating for a long time. But Ismay went up on the bridge and didn’t want his massive investment to sit in the middle of the Atlantic either sinking slowly, or being tugged in to port. Not great publicity! So he told the Captain to go Slow Ahead. Titanic was meant to be unsinkable.’

‘If Titanic had stood still, she would have survived at least until the rescue ship came and no one need have died, but when they drove her ‘Slow Ahead’, the pressure of the sea coming through her damaged hull forced the water over the bulkheads and flooded sequentially one watertight compartment after another – and that was why she sank so fast.’

Why would Patten’s grandfather, a thoroughly honest and brave man, have lied and carried on lying? ‘Because,’ she explains, ‘when he was on the rescue ship, Bruce Ismay pointed out to my grandfather that if he told the truth, the White Star Line would be judged negligent and its limited liability insurance would be invalid. Ismay pretty much said that the whole company would go bust and everyone would lose their jobs. There was a code of honour among men like my grandfather in those days. So he lied to protect others’ jobs.’

So there this secret sat, locked in a family circle from which Patten is now the only survivor.

After all those years of silence, could it really have been that straightforward? ‘Well, not really. This sounds mad, I know, but once I started thinking about it, I felt as if I owed it to the world to share the secret. If I died tomorrow and then it would die with me.’

Good as Gold by Louise Patten (Quercus Publishing Plc) Telegraph Books books.telegraph.co.uk “